Hydrogen peroxide

| Hydrogen peroxide | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

dihydrogen dioxide

|

|

|

Other names

Dioxidane

|

|

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 7722-84-1 |

| PubChem | 784 |

| ChemSpider | 763 |

| EC number | 231-765-0 |

| UN number | 2015 (>60% soln.) 2014 (20–60% soln.) 2984 (8–20% soln.) |

| IUPHAR ligand | 2448 |

| RTECS number | MX0900000 (>90% soln.) MX0887000 (>30% soln.) |

| Properties | |

| Molecular formula | H2O2 |

| Molar mass | 34.0147 g/mol |

| Appearance | Very light blue color; colorless in solution |

| Density | 1.463 g/cm3 |

| Melting point |

-0.43 °C, 273 K, 31 °F |

| Boiling point |

150.2 °C, 423 K, 302 °F |

| Solubility in water | Miscible |

| Solubility | soluble in ether |

| Acidity (pKa) | 11.62 [1] |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.34 |

| Viscosity | 1.245 cP (20 °C) |

| Dipole moment | 2.26 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std enthalpy of formation ΔfH |

-4.007 kJ/g |

| Specific heat capacity, C | 1.267 J/g K (gas) 2.619 J/g K (liquid) |

| Hazards | |

| MSDS | ICSC 0164 (>60% soln.) |

| EU Index | 008-003-00-9 |

| EU classification | Oxidant (O) Corrosive (C) Harmful (Xn) |

| R-phrases | R5, R8, R20/22, R35 |

| S-phrases | (S1/2), S17, S26, S28, S36/37/39, S45 |

| NFPA 704 |

0

3

2

OX

|

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| LD50 | 1518 mg/kg |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds | Water Ozone Hydrazine Hydrogen disulfide |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa) |

|

| Infobox references | |

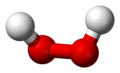

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is a very pale blue liquid, slightly more viscous than water, that appears colorless in dilute solution. It has strong oxidizing properties, and is a powerful bleaching agent. It is used as a disinfectant, antiseptic, oxidizer, and in rocketry as a propellant.[2] The oxidizing capacity of hydrogen peroxide is so strong that it is considered a highly reactive oxygen species.

Hydrogen peroxide is naturally produced in organisms as a by-product of oxidative metabolism. Nearly all living things (specifically, all obligate and facultative aerobes) possess enzymes known as peroxidases, which harmlessly and catalytically decompose low concentrations of hydrogen peroxide to water and oxygen.

Contents |

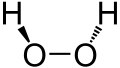

Structure and properties

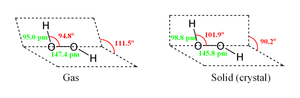

H2O2 adopts a nonplanar structure of C2 symmetry. Although chiral, the molecule undergoes rapid racemization. The flat shape of the anti conformer would minimize steric repulsions, the 90° torsion angle of the syn conformer would optimize mixing between the filled p-type orbital of the oxygen (one of the lone pairs) and the LUMO of the vicinal O-H bond.[3] The observed anticlinal "skewed" shape is a compromise between the two conformers.

Despite the fact that the O-O bond is a single bond, the molecule has a high barrier to complete rotation of 29.45 kJ/mol (compared with 12.5 kJ/mol for the rotational barrier of ethane). The increased barrier is attributed to repulsion between one lone pair and other lone pairs. The bond angles are affected by hydrogen bonding, which is relevant to the structural difference between gaseous and crystalline forms; indeed a wide range of values is seen in crystals containing molecular H2O2.

Comparison with analogues

Analogues of hydrogen peroxide include the chemically identical deuterium peroxide and hydrogen disulfide.[4] Hydrogen disulfide has a boiling point of only 70.7°C despite having a higher molecular weight, indicating that hydrogen bonding increases the boiling point of hydrogen peroxide.

Physical properties of hydrogen peroxide solutions

The properties of aqueous solutions of hydrogen peroxide differ from those of the neat material, reflecting the effects of hydrogen bonding between water and hydrogen peroxide molecules. Hydrogen peroxide and water form a eutectic mixture, exhibiting freezing-point depression. Whereas pure water melts and freezes at approximately 273K, and pure hydrogen peroxide just 0.4K below that, a 50% (by volume) solution melts and freezes at 221 K.[5]

History

Hydrogen peroxide was first isolated in 1818 by Louis Jacques Thénard by reacting barium peroxide with nitric acid.[6] An improved version of this process used hydrochloric acid, followed by sulfuric acid to precipitate the barium sulfate byproduct. Thénard's process was used from the end of the 19th century until the middle of the 20th century.[7] Modern production methods are discussed below.

For a long time, pure hydrogen peroxide was believed to be unstable, because attempts to separate the hydrogen peroxide from the water, which is present during synthesis, failed. This instability was however due to traces of impurities (transition metals salts) that catalyze the decomposition of the hydrogen peroxide. One hundred percent pure hydrogen peroxide was first obtained through vacuum distillation by Richard Wolffenstein in 1894.[8] At the end of 19th century, Petre Melikishvili and his pupil L. Pizarjevski showed that of the many proposed formulas of hydrogen peroxide, the correct one was H-O-O-H.

The use of H2O2 sterilization in biological safety cabinets and barrier isolators is a popular alternative to ethylene oxide (EtO) as a safer, more efficient decontamination method. H2O2 has long been widely used in the pharmaceutical industry. In aerospace research, H2O2 is used to sterilize satellites.

The U.S. FDA has recently granted 510(k) clearance to use H2O2 in individual medical device manufacturing applications. EtO criteria outlined in ANSI/AAMI/ISO 14937 may be used as a validation guideline. Sanyo was the first manufacturer to use the H2O2 process in situ in a cell culture incubator, which is a faster and more efficient cell culture sterilization process.

Manufacture

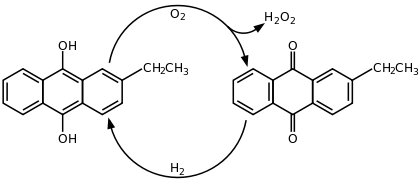

Formerly, hydrogen peroxide was prepared by the electrolysis of an aqueous solution of sulfuric acid or acidic ammonium bisulfate (NH4HSO4), followed by hydrolysis of the peroxodisulfate ((SO4)2)2− that is formed. Today, hydrogen peroxide is manufactured almost exclusively by the autoxidation of a 2-alkyl anthrahydroquinone (or 2-alkyl-9,10-dihydroxyanthracene) to the corresponding 2-alkyl anthraquinone. Major producers commonly use either the 2-ethyl or the 2-amyl derivative. The cyclic reaction depicted below shows the 2-ethyl derivative, where 2-ethyl-9,10-dihydroxyanthracene (C16H14O2) is oxidized to the corresponding 2-ethylanthraquinone (C16H12O2) and hydrogen peroxide. Most commercial processes achieve this by bubbling compressed air through a solution of the anthracene, whereby the oxygen present in the air reacts with the labile hydrogen atoms (of the hydroxy group), giving hydrogen peroxide and regenerating the anthraquinone. Hydrogen peroxide is then extracted and the anthraquinone derivative is reduced back to the dihydroxy (anthracene) compound using hydrogen gas in the presence of a metal catalyst. The cycle then repeats itself.[9][10]

This process is known as the Riedl-Pfleiderer process,[10] having been first discovered by them in 1936. The overall equation for the process is deceptively simple:[9]

- H2 + O2 → H2O2

The economics of the process depend heavily on effective recycling of the quinone (which is expensive) and extraction solvents, and of the hydrogenation catalyst.

In 1994, world production of H2O2 was around 1.9 million tonnes and grew to 2.2 million in 2006,[11] most of which was at a concentration of 70% or less. In that year bulk 30% H2O2 sold for around US $0.54 per kg, equivalent to US $1.50 per kg (US $0.68 per lb) on a "100% basis".

New developments

A new, so-called "high-productivity/high-yield" process, based on an optimized distribution of isomers of 2-amyl anthraquinone, has been developed by Solvay. In July 2008, this process allowed the construction of a "mega-scale" single-train plant in Zandvliet (Belgium). The plant has an annual production capacity more than twice that of the world's next-largest single-train plant. An even-larger plant is scheduled to come onstream at Map Ta Phut (Thailand) in 2011. It can be imagined that this leads to reduction in the cost of production due to economies of scale.[12]

A process to produce hydrogen peroxide directly from the elements has been of interest for many years. The problem with the direct synthesis process is that, in terms of thermodynamics, the reaction of hydrogen with oxygen favors production of water. It had been recognized for some time that a finely dispersed catalyst is beneficial in promoting selectivity to hydrogen peroxide, but, while selectivity was improved, it was still not sufficiently high to permit commercial development of the process. However, an apparent breakthrough was made in the early 2000s by researchers at Headwaters Technology. The breakthrough revolves around development of a minute (nanometer-size) phase-controlled noble metal crystal particles on carbon support. This advance led, in a joint venture with Evonik Industries, to the construction of a pilot plant in Germany in late 2005. It is claimed that there are reductions in investment cost because the process is simpler and involves less equipment; however, the process is also more corrosive and unproven. This process results in low concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (about 5–10 wt% versus about 40 wt% through the anthraquione process).[12]

In 2009, another catalyst development was announced by workers at Cardiff University.[13] This development also relates to the direct synthesis, but, in this case, using gold–palladium nanoparticles. Under normal circumstances, the direct synthesis must be carried out in an acid medium to prevent immediate decomposition of the hydrogen peroxide once it is formed. Whereas hydrogen peroxide tends to decompose on its own (which is why, even after production, it is often necessary to add stabilisers to the commercial product when it is to be transported or stored for long periods), the nature of the catalyst can cause this decomposition to accelerate rapidly. It is claimed that the use of this gold-palladium catalyst reduces this decomposition and, as a consequence, little to no acid is required. The process is in a very early stage of development and currently results in very low concentrations of hydrogen peroxide being formed (less than about 1–2 wt%). Nonetheless, it is envisaged by the inventors that the process will lead to an inexpensive, efficient, and environmentally friendly process.[12][13][14][15]

A novel electrochemical process for the production of alkaline hydrogen peroxide has been developed by Dow. The process employs a monopolar cell to achieve an electrolytic reduction of oxygen in a dilute sodium hydroxide solution.[12]

Availability

Hydrogen peroxide is most commonly available as a solution in water. For consumers, it is usually available from pharmacies at 3 and 6 wt% concentrations. The concentrations are sometimes described in terms of the volume of oxygen gas generated (see decomposition); one milliliter of a 20-volume solution generates twenty milliliters of oxygen gas when completely decomposed. For laboratory use, 30 wt% solutions are most common. Commercial grades from 70% to 98% are also available, but due to the potential of solutions of >68% hydrogen peroxide to be converted entirely to steam and oxygen (with the temperature of the steam increasing as the concentration increases above 68%) these grades are potentially far more hazardous, and require special care in dedicated storage areas. Buyers must typically submit to inspection by the small number of commercial manufacturers.

Reactions

Decomposition

Hydrogen peroxide decomposes (disproportionates) exothermically into water and oxygen gas spontaneously:

- 2 H2O2 → 2 H2O + O2

This process is thermodynamically favorable. It has a ΔHo of −98.2 kJ·mol−1 and a ΔGo of −119.2 kJ·mol−1 and a ΔS of 70.5 J·mol−1·K−1. The rate of decomposition is dependent on the temperature and concentration of the peroxide, as well as the pH and the presence of impurities and stabilizers. Hydrogen peroxide is incompatible with many substances that catalyse its decomposition, including most of the transition metals and their compounds. Common catalysts include manganese dioxide and silver. The same reaction is catalysed by the enzyme catalase, found in the liver, whose main function in the body is the removal of toxic byproducts of metabolism and the reduction of oxidative stress. The decomposition occurs more rapidly in alkali, so acid is often added as a stabilizer.

The liberation of oxygen and energy in the decomposition has dangerous side-effects. Spilling high concentrations of hydrogen peroxide on a flammable substance can cause an immediate fire, which is further fueled by the oxygen released by the decomposing hydrogen peroxide. High test peroxide, or HTP (also called high-strength peroxide) must be stored in a suitable, vented container to prevent the buildup of oxygen gas, which would otherwise lead to the eventual rupture of the container.

In the presence of certain catalysts, such as Fe2+ or Ti3+, the decomposition may take a different path, with free radicals such as HO· (hydroxyl) and HOO· being formed. A combination of H2O2 and Fe2+ is known as Fenton's reagent.

A common concentration for hydrogen peroxide is 20-volume, which means that, when 1 volume of hydrogen peroxide is decomposed, it produces 20 volumes of oxygen. A 20-volume concentration of hydrogen peroxide is equivalent to 1.667 mol/dm3 (Molar solution) or about 6%.

Redox reactions

In acidic solution, H2O2 is one of the most powerful oxidizers known—stronger than chlorine, chlorine dioxide, and potassium permanganate. Also, through catalysis, H2O2 can be converted into hydroxyl radicals (.OH), which are highly reactive.

| Oxidant/Reduced product | Oxidation potential, V |

|---|---|

| Fluorine/Hydrogen fluoride | 3.0 |

| Ozone/Oxygen | 2.1 |

| Hydrogen peroxide/Water | 1.8 |

| Potassium permanganate/Manganese dioxide | 1.7 |

| Chlorine dioxide/HClO | 1.5 |

| Chlorine/Chloride | 1.4 |

In aqueous solution, hydrogen peroxide can oxidize or reduce a variety of inorganic ions. When it acts as a reducing agent, oxygen gas is also produced.

In acidic solutions Fe2+ is oxidized to Fe3+ (hydrogen peroxide acting as an oxidizing agent),

and sulfite (SO32−) is oxidized to sulfate (SO42−). However, potassium permanganate is reduced to Mn2+ by acidic H2O2. Under alkaline conditions, however, some of these reactions reverse; for example, Mn2+ is oxidized to Mn4+ (as MnO2).

Another example of hydrogen peroxide's acting as a reducing agent is the reaction with sodium hypochlorite, which is a convenient method for preparing oxygen in the laboratory.

- NaOCl + H2O2 → O2 + NaCl + H2O

Hydrogen peroxide is frequently used as an oxidizing agent in organic chemistry. One application is for the oxidation of thioethers to sulfoxides. For example, methyl phenyl sulfide was oxidized to methyl phenyl sulfoxide in 99% yield in methanol in 18 hours (or 20 minutes using a TiCl3 catalyst):

- Ph-S-CH3 + H2O2 → Ph-S(O)-CH3 + H2O

Alkaline hydrogen peroxide is used for epoxidation of electron-deficient alkenes such as acrylic acids, and also for oxidation of alkylboranes to alcohols, the second step of hydroboration-oxidation.

Formation of peroxide compounds

Hydrogen peroxide is a weak acid, and it can form hydroperoxide or peroxide salts or derivatives of many metals.

For example, on addition to an aqueous solution of chromic acid (CrO3) or acidic solutions of dichromate salts, it will form an unstable blue peroxide CrO(O2)2. In aqueous solution it rapidly decomposes to form oxygen gas and chromium salts.

It can also produce peroxoanions by reaction with anions; for example, reaction with borax leads to sodium perborate, a bleach used in laundry detergents:

- Na2B4O7 + 4 H2O2 + 2 NaOH → 2 Na2B2O4(OH)4 + H2O

H2O2 converts carboxylic acids (RCOOH) into peroxy acids (RCOOOH), which are themselves used as oxidizing agents. Hydrogen peroxide reacts with acetone to form acetone peroxide, and it interacts with ozone to form hydrogen trioxide, also known as trioxidane. Reaction with urea produces carbamide peroxide, used for whitening teeth. An acid-base adduct with triphenylphosphine oxide is a useful "carrier" for H2O2 in some reactions.

Alkalinity

Hydrogen peroxide is a much weaker base than water, but it can still form adducts with very strong acids. The superacid HF/SbF5 forms unstable compounds containing the [H3O2]+ ion.

Uses

Industrial applications

About 50% of the world's production of hydrogen peroxide in 1994 was used for pulp- and paper-bleaching.[11] Other bleaching applications are becoming more important as hydrogen peroxide is seen as an environmentally benign alternative to chlorine-based bleaches.

Other major industrial applications for hydrogen peroxide include the manufacture of sodium percarbonate and sodium perborate, used as mild bleaches in laundry detergents. It is used in the production of certain organic peroxides such as dibenzoyl peroxide, used in polymerisations and other chemical processes. Hydrogen peroxide is also used in the production of epoxides such as propylene oxide. Reaction with carboxylic acids produces a corresponding peroxy acid. Peracetic acid and meta-chloroperoxybenzoic acid (commonly abbreviated mCPBA) are prepared from acetic acid and meta-chlorobenzoic acid, respectively. The latter is commonly reacted with alkenes to give the corresponding epoxide.

In the PCB manufacturing process, hydrogen peroxide mixed with sulfuric acid was used as the microetch chemical for copper surface roughening preparation.

A combination of a powdered precious metal-based catalyst, hydrogen peroxide, methanol and water can produce superheated steam in one to two seconds, releasing only CO2 and high-temperature steam for a variety of purposes.[16]

Recently, there has been increased use of vaporized hydrogen peroxide in the validation and bio-decontamination of half-suit and glove-port isolators in pharmaceutical production.

Nuclear pressurized water reactors (PWRs) use hydrogen peroxide during the plant shutdown to force the oxidation and dissolution of activated corrosion products deposited on the fuel. The corrosion products are then removed with the cleanup systems before the reactor is disassembled.

Hydrogen peroxide is also used in the oil and gas exploration industry to oxidize rock matrix in preparation for micro-fossil analysis.

Chemical applications

A method of producing propylene oxide from hydrogen peroxide has been developed. The process is claimed to be environmentally friendly, since the only significant byproduct is water. It is also claimed the process has significantly lower investment and operating costs. Two of these "HPPO" (hydrogen peroxide to propylene oxide) plants came onstream in 2008: One of them located in Belgium is a Solvay, Dow-BASF joint venture, and the other in Korea is a EvonikHeadwaters, SK Chemicals joint venture. A caprolactam application for hydrogen peroxide has been commercialized. Potential routes to phenol and epichlorohydrin utilizing hydrogen peroxide have been postulated.[12]

Biological function

Hydrogen peroxide is also one of the two chief chemicals in the defense system of the bombardier beetle, reacting with hydroquinone to discourage predators.

A study published in Nature found that hydrogen peroxide plays a role in the immune system. Scientists found that hydrogen peroxide is released after tissues are damaged in zebra fish, which is thought to act as a signal to white blood cells to converge on the site and initiate the healing process. When the genes required to produce hydrogen peroxide were disabled, white blood cells did not accumulate at the site of damage. The experiments were conducted on fish; however, because fish are genetically similar to humans, the same process is speculated to occur in humans. The study in Nature suggested Asthma sufferers have higher levels of hydrogen peroxide in their lungs than healthy people, which could be explained by asthma sufferers having inappropriate levels of white blood cells in their lungs.[17][18]

Domestic uses

- Diluted H2O2 (between 3% and 12%) is used to bleach human hair when mixed with ammonium hydroxide, hence the phrase "peroxide blonde".

- It is absorbed by skin upon contact and creates a local skin capillary embolism that appears as a temporary whitening of the skin.

- It is used to whiten bones that are to be put on display.

- 3% H2O2 is used medically for cleaning wounds, removing dead tissue, and as an oral debriding agent. Peroxide stops slow (small vessel) wound bleeding/oozing, as well. However, recent studies have suggested that hydrogen peroxide impedes scarless healing as it destroys newly formed skin cells.[19] Most over-the-counter peroxide solutions are not suitable for ingestion.

- If a dog has swallowed a harmful substance (e.g., rat poison), small amounts of hydrogen peroxide can be given to induce vomiting.[20]

- 3% H2O2 is effective at treating fresh (red) blood-stains in clothing and on other items. It must be applied to clothing before blood stains can be accidentally "set" with heated water. Cold water and soap are then used to remove the peroxide treated blood.

- The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has classified hydrogen peroxide as a Low Regulatory Priority (LRP) drug for use in controlling fungus on fish and fish eggs. (See ectoparasite.)

- Some horticulturalists and users of hydroponics advocate the use of weak hydrogen peroxide solution in watering solutions. Its spontaneous decomposition releases oxygen that enhances a plant's root development and helps to treat root rot (cellular root death due to lack of oxygen) and a variety of other pests.[21][22] There is some peer-reviewed academic research to back up some of the claims.[23]

- Laboratory tests conducted by fish culturists in recent years have demonstrated that common household hydrogen peroxide can be used safely to provide oxygen for small fish.[24][25] Hydrogen peroxide releases oxygen by decomposition when it is exposed to catalysts such as manganese dioxide.

- Hydrogen peroxide is a strong oxidizer effective in controlling sulfide and organic-related odors in wastewater collection and treatment systems. It is typically applied to a wastewater system where there is a retention time of 30 minutes to 5 hours before hydrogen sulfide is released. Hydrogen peroxide oxidizes the hydrogen sulfide and promotes bio-oxidation of organic odors. Hydrogen peroxide decomposes to oxygen and water, adding dissolved oxygen to the system, thereby negating some Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD).

- Mixed with baking soda and a small amount of hand soap, hydrogen peroxide is effective at removing skunk odor.[26]

- Hydrogen peroxide is used with phenyl oxalate ester and an appropriate dye in glow sticks as an oxidizing agent. It reacts with the ester to form an unstable CO2 dimer, which excites the dye to an excited state; the dye emits a photon (light) when it spontaneously relaxes back to the ground state.

Use as propellant

High concentration H2O2 is referred to as HTP or High test peroxide. It can be used either as a monopropellant (not mixed with fuel) or as the oxidizer component of a bipropellant rocket. Use as a monopropellant takes advantage of the decomposition of 70–98+% concentration hydrogen peroxide into steam and oxygen. The propellant is pumped into a reaction chamber where a catalyst, usually a silver or platinum screen, triggers decomposition, producing steam at over 600 °C, which is expelled through a nozzle, generating thrust. H2O2 monopropellant produces a maximum specific impulse (Isp) of 161 s (1.6 kN·s/kg), which makes it a low-performance monopropellant. Peroxide generates much less thrust than hydrazine, but is not toxic. The Bell Rocket Belt used hydrogen peroxide monopropellant.

As a bipropellant H2O2 is decomposed to burn a fuel as an oxidizer. Specific impulses as high as 350 s (3.5 kN·s/kg) can be achieved, depending on the fuel. Peroxide used as an oxidizer gives a somewhat lower Isp than liquid oxygen, but is dense, storable, noncryogenic and can be more easily used to drive gas turbines to give high pressures using an efficient closed cycle. It can also be used for regenerative cooling of rocket engines. Peroxide was used very successfully as an oxidizer in World-War-II German rockets (e.g. T-Stoff, containing oxyquinoline stabilizer, for the Me-163), and for the low-cost British Black Knight and Black Arrow launchers.

In the 1940s and 1950s, the Walter turbine used hydrogen peroxide for use in submarines while submerged; it was found to be too noisy and require too much maintenance compared to diesel-electric power systems. Some torpedoes used hydrogen peroxide as oxidizer or propellant, but this was dangerous and has been discontinued by most navies. Hydrogen peroxide leaks were blamed for the sinkings of HMS Sidon and the Russian submarine Kursk. It was discovered, for example, by the Japanese Navy in torpedo trials, that the concentration of H2O2 in right-angle bends in HTP pipework can often lead to explosions in submarines and torpedoes. SAAB Underwater Systems is manufacturing the Torpedo 2000. This torpedo, used by the Swedish navy, is powered by a piston engine propelled by HTP as an oxidizer and kerosene as a fuel in a bipropellant system.[27]

While rarely used now as a monopropellant for large engines, small hydrogen peroxide attitude control thrusters are still in use on some satellites. They are easy to throttle, and safer to fuel and handle before launch than hydrazine thrusters. However, hydrazine is more often used in spacecraft because of its higher specific impulse and lower rate of decomposition.

Therapeutic use

Hydrogen peroxide is generally recognized as safe (GRAS) as an antimicrobial agent, an oxidizing agent and for other purposes by the FDA.[28]

Hydrogen peroxide has been used as an antiseptic and anti-bacterial agent for many years due to its oxidizing effect. While its use has decreased in recent years with the popularity of readily available over the counter products, it is still used by many hospitals, doctors and dentists.

- Like many oxidative antiseptics, hydrogen peroxide causes mild damage to tissue in open wounds, but it also is effective at rapidly stopping capillary bleeding (slow blood oozing from small vessels in abrasions), and is sometimes used sparingly for this purpose, as well as cleaning.

- Hydrogen peroxide can be used as a toothpaste when mixed with correct quantities of baking soda and salt.[29]

- Hydrogen peroxide and benzoyl peroxide are sometimes used to treat acne.[30]

- Hydrogen peroxide is used as an emetic in veterinary practice.[31]

- Alternative uses

- The American Cancer Society states that "there is no scientific evidence that hydrogen peroxide is a safe, effective or useful cancer treatment", and advises cancer patients to "remain in the care of qualified doctors who use proven methods of treatment and approved clinical trials of promising new treatments." [32]

- Another controversial alternative medical procedure is inhalation of hydrogen peroxide at a concentration of about 1%. Intravenous usage of hydrogen peroxide has been linked to several deaths.[33][34]

- Advocates of internal use say that they never use "High Concentration" but only diluted. The confusion arises because of the use of High Purity "Food Grade" Hydrogen peroxide which is commonly only sold in bulk concentrations of 35% to industry and is used because it is approved for internal use in food preparation by the FDA. But it is NEVER used at the concentration of 35% or even 1% to 3% internally. Hydrogen Peroxide when used internally is diluted down to strengths of less of than 0.1% (ie adding 2-20 drops per 6-8 ounce (250ml) of distilled or spring water).[35]

- See also Liquid Oxygen (supplement)

Safety

Regulations vary, but low concentrations, such as 3%, are widely available and legal to buy for medical use. Higher concentrations may be considered hazardous and are typically accompanied by a Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS). In high concentrations, hydrogen peroxide is an aggressive oxidizer and will corrode many materials, including human skin. In the presence of a reducing agent, high concentrations of H2O2 will react violently.

High-concentration hydrogen peroxide streams, typically above 40%, should be considered a D001 hazardous waste, due to concentrated hydrogen peroxide's meeting the definition of a DOT oxidizer, if released into the environment. The EPA Reportable Quantity (RQ) for D001 hazardous wastes is 100 pounds, or approximately ten gallons, of concentrated hydrogen peroxide.

Hydrogen peroxide should be stored in a cool, dry, well-ventilated area and away from any flammable or combustible substances.[36] It should be stored in a container composed of non-reactive materials such as stainless steel or glass (other materials including some plastics and aluminium alloys may also be suitable).[37] Because it breaks down quickly when exposed to light, it should be stored in an opaque container, and pharmaceutical formulations typically come in brown bottles that filter out light.[38]

Hydrogen peroxide, either in pure or diluted form, can pose several risks:

- Explosive vapors. Above roughly 70% concentrations, hydrogen peroxide can give off vapor that can detonate above 70 °C (158 °F) at normal atmospheric pressure. This can then cause a boiling liquid expanding vapor explosion (BLEVE) of the remaining liquid. Distillation of hydrogen peroxide at normal pressures is thus highly dangerous.

- Hazardous reactions. Hydrogen peroxide vapors can form sensitive contact explosives with hydrocarbons such as greases. Hazardous reactions ranging from ignition to explosion have been reported with alcohols, ketones, carboxylic acids (particularly acetic acid), amines and phosphorus.

- Spontaneous ignition. Concentrated hydrogen peroxide, if spilled on clothing (or other flammable materials), will preferentially evaporate water until the concentration reaches sufficient strength, at which point the material may spontaneously ignite.[39][40]

- Corrosive. Concentrated hydrogen peroxide (>50%) is corrosive, and even domestic-strength solutions can cause irritation to the eyes, mucous membranes and skin.[41] Swallowing hydrogen peroxide solutions is particularly dangerous, as decomposition in the stomach releases large quantities of gas (10 times the volume of a 3% solution) leading to internal bleeding. Inhaling over 10% can cause severe pulmonary irritation.

- Bleach agent. Low concentrations of hydrogen peroxide, on the order of 3% or less, will chemically bleach many types of clothing to a pinkish hue. Caution should be exercised when using common products that may contain hydrogen peroxide, such as facial cleaner or contact lens solution, which easily splatter upon other surfaces.

- Internal ailments. Large oral doses of hydrogen peroxide at a 3% concentration may cause "irritation and blistering to the mouth, (which is known as Black hairy tongue) throat, and abdomen", as well as "abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea".[42]

- Vapor pressure. Hydrogen peroxide has a significant vapor pressure (1.2 kPa at 50 oC[CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 76th Ed, 1995-1996]) and exposure to the vapor is potentially hazardous. Hydrogen peroxide vapor is a primary irritant, primarily affecting the eyes and respiratory system and the NIOSH Immediately dangerous to life and health limit (IDLH) is only 75 ppm. Documentation for Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH): NIOSH [http://www.cdc.gov/NIOSH/National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health] Chemical Listing and Documentation of Revised IDLH Values (as of 3/1/95). Long term exposure to low ppm concentrations is also hazardous and can result in permanent lung damage and OSHA Occupational Safety and Health Administration has established a permissible exposure limit of 1.0 ppm calculated as an eight hour time weighted average (29 CFR 1910.1000, Table Z-1) and hydrogen peroxide has also been classified by the ACGIH American Conference of Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) as a "known animal carcinogen, with unknown relevance on humans.[2008 Threshold Limit Values for Chemical Substances and Physical Agents & Biological Exposure Indices, ACGIH] In applications where high concentrations of hydrogen peroxide are used, suitable personal protective equipment should be worn and it is prudent in situations where the vapor is likely to be generated, such as hydrogen peroxide gas or vapor sterilization, to ensure that there is adequate ventilation and the vapor concentration monitored with a continuous gas monitor for hydrogen peroxide. Continuous gas monitors for hydrogen peroxide are available from several suppliers. Further information on the hazards of hydrogen peroxide is available from OSHA Occupational Safety and Health Guideline for Hydrogen Peroxide and from the ATSDR. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry

- Skin disorders. Vitiligo is an acquired skin disorder with the loss of native skin pigment, which affects about 0.5-1% of the world population. Recent studies have discovered increased H2O2 levels in the epidermis and in blood are one of many hallmarks of this disease.[43]

Historical incidents

- On July 16, 1934 in Kummersdorf, Germany a rocket engine using hydrogen peroxide exploded, killing three people. As a result of this incident, Werner von Braun decided not to use hydrogen peroxide as an oxidizer in the rockets he developed afterward.

- Several people received minor injuries after a hydrogen peroxide spill on board Northwest Airlines flight 957 from Orlando to Memphis on October 28, 1998 and subsequent fire on Northwest Airlines flight 7.[44]

- During the Second World War, doctors in Nazi concentration camps experimented with the use of hydrogen peroxide injections in the killing of human subjects.[45]

- Hydrogen peroxide was said to be one of the ingredients in the bombs that failed to explode in the July 21, 2005 London bombings.[46]

- The Russian submarine K-141 Kursk sailed out to sea to perform an exercise of firing dummy torpedoes at the Pyotr Velikiy, a Kirov class battlecruiser. On August 12, 2000 at 11:28 local time (07:28 UTC), there was an explosion while preparing to fire the torpedoes. The only credible report to date is that this was due to the failure and explosion of one of the Kursk's hydrogen peroxide-fueled torpedoes. It is believed that HTP, a form of highly concentrated hydrogen peroxide used as propellant for the torpedo, seeped through rust in the torpedo casing. A similar incident was responsible for the loss of HMS Sidon in 1955

- On August 16th, 2010 a spill of about 10 gallons of cleaning fluid spilled on the 53rd floor of 1515 Broadway, in Times Square, New York City. The spill, which a spokesperson for the New York City fire department said was of Hydrogen Peroxide, shut down Broadway between West 42nd and West 48th streets as a number of fire engines responded to the hazmat situation. There were no reported injuries. [47]

References

Notes

- ↑ Pradyot Patnaik. Handbook of Inorganic Chemicals. McGraw-Hill, 2002, ISBN 0-07-049439-8

- ↑ Hill, C. N. (2001). A Vertical Empire: The History of the UK Rocket and Space Programme, 1950-1971. Imperial College Press. ISBN 9781860942686. http://books.google.com/?id=AzoCJfTmRDsC.

- ↑ Dougherty, Dennis A.; Eric V. Anslyn (2005). Modern Physical Organic Chemistry. University Science. p. 122. ISBN 1-891389-31-9.

- ↑ Landolt-Börnstein Substance - Property Index

- ↑ 60% hydrogen peroxide msds 50% H2O2 MSDS

- ↑ L. J. Thenard (1818). Annales de chimie et de physique 8: 308.

- ↑ C. W. Jones, J. H. Clark. Applications of Hydrogen Peroxide and Derivatives. Royal Society of Chemistry, 1999.

- ↑ Richard Wolffenstein (1894). "Concentration und Destillation von Wasserstoffsuperoxyd". Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft 27 (3): 3307–3312. doi:10.1002/cber.189402703127.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Jose M. Campos-Martin, Gema Blanco-Brieva, Jose L. G. Fierro (2006). "Hydrogen Peroxide Synthesis: An Outlook beyond the Anthraquinone Process". Angewandte Chemie International Edition 45 (42): 6962–6984. doi:10.1002/anie.200503779. PMID 17039551.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 H. Riedl and G. Pfleiderer, U.S. Patent 2,158,525 (October 2, 1936 in USA, and October 10, 1935 in Germany) to I. G. Farbenindustrie, Germany

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Ronald Hage, Achim Lienke (2005). "Applications of Transition-Metal Catalysts to Textile and Wood-Pulp Bleaching". Angewandte Chemie International Edition 45 (2): 206–222. doi:10.1002/anie.200500525. PMID 16342123.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Hydrogen Peroxide 07/08-03 Report, ChemSystems, May 2009.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 G.J. Hutchings et al, Science, 2009, 323, 1037

- ↑ "Gold-palladium Nanoparticles Achieve Greener, Smarter Production Of Hydrogen Peroxide". Sciencedaily.com. 2009-03-03. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/02/090219141507.htm. Retrieved 2010-09-05.

- ↑ Jennifer K. Edwards, Benjamin Solsona, Edwin Ntainjua N, Albert F. Carley (Feb 2009). "Switching off hydrogen peroxide hydrogenation in the direct synthesis process.". Science 323 (5917): 1037–41. doi:10.1126/science.1168980. PMID 19229032.

- ↑ Instant steam puts heat on MRSA, Society Of Chemical Industry

- ↑ "Natural bleach 'key to healing'". BBC News. 6 June 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/8078525.stm. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ↑ Niethammer, Philipp; Clemens Grabher, A. Thomas Look & Timothy J. Mitchison (3 June 2009). "A tissue-scale gradient of hydrogen peroxide mediates rapid wound detection in zebrafish". Nature 459 (7249): 996–999. doi:10.1038/nature08119. ISSN doi=10.1038/nature08119. PMID 19494811. PMC 2803098. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v459/n7249/full/nature08119.html. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ↑ "Hydrogen peroxide disrupts scarless fetal wound repair". Cat.inist.fr. http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=17151171. Retrieved 2010-09-05.

- ↑ How to Induce Vomiting (Emesis) in Dogs

- ↑ Fredrickson, Bryce. "Hydrogen Peroxide and Horticulture". http://www.socalplumeriacare.com/Faqs/F-7.pdf. Retrieved 2009-01-25.

- ↑ Ways to use hydrogen peroxide in the garden

- ↑ Oxygation Unlocks Yield Potentials of Crops in Oxygen-Limited Soil Environments Advances in Agronomy, Volume 88, 2005, Pages 313-377 Surya P. Bhattarai, Ninghu Su, David J. Midmore

- ↑ Great-lakes.org

- ↑ fws.gov

- ↑ Chemist Paul Krebaum claims to have originated the formula for use on skunked pets at Skunk Remedy

- ↑ Scott, Richard (November, 1997). "Homing Instincts". Jane's Navy Steam generated by catalytic decomposition of 80-90 % hydrogen peroxide was used for driving the turbopump turbines of the V-2 rockets, the X-15 rocketplanes, the early Centaur RL-10 engines and is still used on Soyuz for that purpose to-day. International. http://babriet.tripod.com/articles/art_hominginstinct.htm.

- ↑ "Sec. 184.1366 Hydrogen peroxide". U.S. Government Printing Office via GPO Access. 2001-04-01. http://a257.g.akamaitech.net/7/257/2422/04nov20031500/edocket.access.gpo.gov/cfr_2001/aprqtr/21cfr184.1366.htm. Retrieved 2007-07-07.

- ↑ Shepherd, Steven. "Brushing Up on Gum Disease". FDA Consumer. http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/CONSUMER/CON00065.html. Retrieved 2007-07-07.

- ↑ Milani, Massimo; Bigardi, Andrea; Zavattarelli, Marco (2003). "Efficacy and safety of stabilised hydrogen peroxide cream (Crystacide) in mild-to-moderate acne vulgaris: a randomised, controlled trial versus benzoyl peroxide gel". Current Medical Research and Opinion 19 (2): 135–138(4). doi:10.1185/030079902125001523. PMID 12740158. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/452990.

- ↑ "Drugs to Control or Stimulate Vomiting". Merck Veterinary manual. Merck & Co., Inc. 2006. http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/index.jsp?cfile=htm/bc/190303.htm.

- ↑ "Questionable methods of cancer management: hydrogen peroxide and other 'hyperoxygenation' therapies". CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 43 (1): 47–56. 1993. doi:10.3322/canjclin.43.1.47. PMID 8422605.

- ↑ Cooper, Anderson (2005-01-12). "A Prescription for Death?". CBS News. http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2005/01/12/60II/main666489.shtml. Retrieved 2007-07-07.

- ↑ Mikkelson, Barbara (2006-04-30). "Hydrogen Peroxide". Snopes.com. http://www.snopes.com/medical/healthyself/peroxide.asp. Retrieved 2007-07-07.

- ↑

- ↑ Hydrogen Peroxide MSDS

- ↑ Ozonelab Peroxide compatibility

- ↑ "The Many Uses of Hydrogen Peroxide-Truth! Fiction! Unproven!". http://www.truthorfiction.com/rumors/h/hydrogen-peroxide.htm. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- ↑ NTSB - Hazardous Materials Incident Brief

- ↑ Armadilloaerospace material tests with HTP

- ↑ For example, see an MSDS for a 3% peroxide solution.

- ↑ Hydrogen Peroxide, 3%. 3. Hazards Identification Southeast Fisheries Science Center, daughter agency of NOAA.

- ↑ "forschung". Vitiligo.eu.com. http://www.vitiligo.eu.com/turmeric.htm. Retrieved 2010-09-05.

- ↑ Hazardous Materials Incident Brief DCA-99-MZ-001, "Spill of undeclared shipment of hazardous materials in cargo compartment of aircraft". pub: National Transportation Safety Board. October 28, 1998; adopted May 17, 2000.

- ↑ "The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide". Robert Jay Lifton. http://www.holocaust-history.org/lifton/LiftonT257.shtml. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ↑ Four Men Found Guilty in Plot to Blow Up London's Transit System, "FOXNews.com". (July 9, 2007)

- ↑ Times Sq. cleaning fluid spill brings fire trucks, [1]. (August 17, 2010)

Bibliography

- J. Drabowicz et al., in The Syntheses of Sulphones, Sulphoxides and Cyclic Sulphides, p112-116, G. Capozzi et al., eds., John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, UK, 1994. ISBN 0-471-93970-6.

- N. N. Greenwood, A. Earnshaw, Chemistry of the Elements, 2nd ed., Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, UK, 1997. A great description of properties & chemistry of H2O2.

- J. March, Advanced Organic Chemistry, 4th ed., p. 723, Wiley, New York, 1992.

- W. T. Hess, Hydrogen Peroxide, in Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology, 4th edition, Wiley, New York, Vol.13, 961-995 (1995).

External links

- Hydrogen Peroxide Distillation for rocket fuel

- Material Safety Data Sheet

- ATSDR Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry FAQ

- Negative effects of Hydrogen Peroxide as an oral rinse

- Food Grade Hydrogen Peroxide Information

- Experimental Rocket Propulsion Society

- International Chemical Safety Card 0164

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- IARC Monograph "Hydrogen Peroxide"

- General Kinetics Inc. Hydrogen Peroxide Rocket Engines and Gas Generators

- Oxygenation Therapy:Unproven Treatments for Cancer and AIDS

- Hydrogen Peroxide in the Human Body

- Information on many common uses for hydrogen peroxide, especially household uses.

- Hydrogen peroxide in tooth whiteners summary by GreenFacts of the European Commission SCCP assessment

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||